In the Cooperation Lab at Boston College, we study the developmental roots of cooperation. One question of particular interest to our team is how fairness influences children’s behavior in the context of cooperation. One approach we use to address this question consists of presenting children with intuitive, child-friendly versions of economic games. One example of this is the Inequity Game, a game in which participants are paired with a partner and can choose to accept or reject resource allocations that are either equally or unequally distributed. Previous work has revealed some interesting findings about children’s fairness behavior in this context. For example, children’s behavior seems to vary across development, with younger children refusing allocations that place them at a disadvantage relative to peers (called disadvantageous inequity aversion) while older children rejecting both these allocations as well as those that place them at an advantage relative to peers (called advantageous inequity aversion; reviewed in McAuliffe et al., 2017). More recently, we learned that children are more likely to reject advantageous inequity offers when the partner is aware of their behavior (McAuliffe et al., 2020). To us, this suggests that children are using rejections of advantageous allocations to signal something to their partner. If this is true, it then follows that partners will pay attention to and use this signal. In the current study, recently published in Scientific Reports (Prétôt et al., 2020), we tackled this question: do children use inequity aversion as a signal of partner quality and does this information influence their subsequent behavior in a cooperative context.

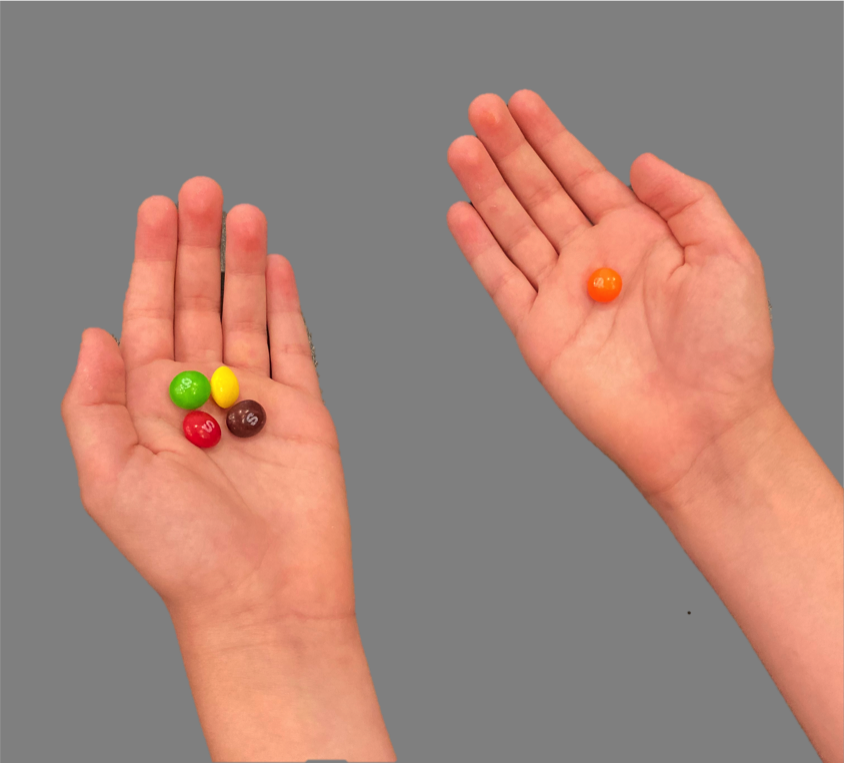

In our study, 6- to 9-year-old children learned about other children who had either accepted or rejected allocations of candy. They then had a chance to play a Prisoner’s Dilemma—a one-shot cooperative game—with either the acceptor or rejector. We thought children would be especially likely to choose to partner with rejectors of advantageous inequity and that they would then be likely to cooperate with them. Contrary to our predictions, however, children did not preferentially use information about fairness when choosing a partner, nor did they appear to use this information when deciding whether to cooperate in the game, suggesting that children prefer efficient over fair partners. These findings are particularly intriguing because they are at odds with how children actually behave in the Inequity Game. If children use fairness as a public and costly signal, why is this not used more widely in partner choice context? In this paper, we examine both theoretical and pragmatic reasons that could explain these results.

One of the things that makes this study novel is that we married methods from both the Inequity Game as well as the Prisoner’s Dilemma, asking how fairness influences cooperation. As such, it represents an important step toward better understanding the links between partner choice decisions, fairness, and cooperation in child development.

Authors: Laurent Prétôt, Gorana Gonzalez, and Katherine McAuliffe.

Article link: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65452-9

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in