https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0783-3

The experimental paradigm to study the tragedy of the commons is the public goods game. Imagine 4 students who are asked to contribute anonymously €1 each or nothing in each of several rounds. After each round the collected money is doubled and redistributed among all players irrespective of whether they contributed. If all contributed, they have a net gain of €1 each. However, the first one not contributing earns €1.50, the others only €0.50 net each. Thus, cooperation in these games usually collapses quickly: free riders dominate.

Cooperation can be maintained if the public goods game is combined with another game, in which a good reputation is needed to earn money. Students had the same pseudonym in both games. The need to maintain good reputation solved the tragedy of the commons, but only as long as the other game existed. Thereafter cooperation collapsed (2). This was a key experience when we played this game with students at Hamburg University. It opened new perspectives for addressing preserving the global climate. All people on earth take part in this natural public goods game. To be tractable it would be necessary to simplify climate change mitigation in an experimental economic game.

At a reception offered by the mayor of Hamburg to the members of the Max Planck Society at their annual meeting, I happened, walking with a glass of wine, to meet someone else with a glass of wine and a name badge from the MPI of Meteorology, who, to my surprise, said he knows our cooperation research. Jochem Marotzke and I agreed quickly to join forces to study human behaviour toward climate change.

In our first project we studied whether reputation would help solving also the climate public goods game. Here the money assembled after each round in the collected pool was, after doubling, not redistributed among the players but used for an advertisement informing about climate change in a daily newspaper. When the students acted anonymously without their pseudonym, they invested close to nothing. But under their pseudonym, recognizable in the reputation game, they contributed a lot (3). People will invest more in sustaining the climate, when they do it in public.

Next we simulated the essential features of the dangerous climate change game in a ‘nutshell’: will a group of people reach a fixed target sum through successive individual monetary contributions, when they know they will lose all their remaining money, if the group fails to reach the target? Each of 6 students was asked to contribute €0, 2 or 4 per round from their endowment of €40 each to the climate account. They knew that each would receive in cash all the remained money in their account, if the group as a whole had contributed at least €120 after 10 rounds, averting simulated dangerous climate change. Upon failure all money would be lost with a probability of 90%. As in the real game, free riding was common: Even though it paid to invest, half of the groups missed the target (4). With this design the ‘collective risk social dilemma’ was born. It has been used as a ‘workhorse’ by other groups and by us to study various problems of climate change mitigation. Most results were frustrating because they mirrored reality, e.g. groups did not succeed to ‘rescue’ the climate for the next generation by investing toward a target for planting CO2 storing oak trees (5). Discounting of the future and the global dilution of the gain takes their toll.

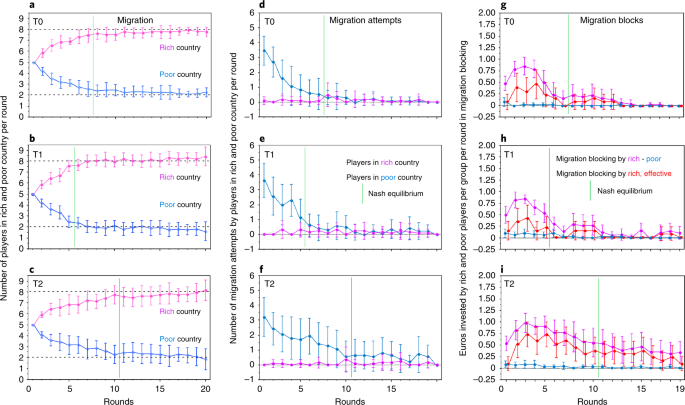

Poverty and climate migration have become a burning problem, often in combination. In 2018, approximately 16 million people were displaced by floods, extreme storms, droughts and wildfires (6). Our present study (7) staged the situation of people in a rich and a poor country, the latter being hit by randomly occurring extreme events destroying their harvest for 3 of the 20 rounds of the game. The rich had twice the harvest per round as the poor at the start. Up to one poor inhabitant per round could migrate to the rich country, if the rich did not block migration by individually investing toward a target sum. Free-riding among the rich, when cooperation would have been required to prevent migration, suggests that climate-induced migration to richer countries is all but inevitable. Upon successful migration the individual harvest decreased in the rich country, and increased in the poor country, until people had reached a Nash distribution with same harvest in either country as always happened. In each round all players could invest from their low or rich endowment towards a target sum for averting ‘dangerous climate change’ to be assembled after 20 rounds. The rich were willing to increase their effort when the poor were hit by a climate extreme event exacerbating their poverty. When compared to a treatment without climate events, more migration and more blocking attempts occurred in addition to mere poverty migration. Surprisingly, a threshold emerged, a minimum contribution by the rich above which the poor are willing to compensate some reduced effort by the rich toward the mitigation target, suggesting some hope for global cooperation. Thus, the economically powerful need to go ahead in the global effort to avert dangerous climate change, and the poor might follow.

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243-1248 (1968).

- Milinski, M., Semmann, D., Krambeck, H.-J. Reputqtion helps solve the ‘tragedy of the commons’. Nature 415,424-426 (2002).

- Milinski, M., Semmann, D., Krambeck, H.-J., Marotzke, J. Stabilizing the Earth’s climate is not a losing game: Supporting evidence from public goods experiments. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3994–3998, (2006).

- Milinski, M., Sommerfeld, R. D., Krambeck, H.-J., Reed, F. A., Marotzke, J. The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2291-2294 (2008).

- Jacquet, J., Hagel, K., Hauert, C., Marotzke, J., Röhl, T., Milinski, M. Intra- and intergenerational discounting in the climate game. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 1025-1028 (2013). DOI 10.1038/s41558-020-0783-3.

- McLeman, R. International migration and climate adaptation in an era of hardening borders. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 911-918 (2019).

-

Marotzke, J., Semmann, D., Milinski, M. The economic

interaction between climate change mitigation, climate migration, and poverty. Nat. Clim. Change (2020). DOI 10.1038/s41558-020-0783-3.

Fig. 1 | a Migration starting from 5 players in rich and 5 in poor country of 14 groups with 10 players each. Stippled lines show numbers of inhabitants corresponding to Nash equilibrium, green line shows the round when Nash equilibrium is reached on average, b Migration attempts per group and round, c Euros invested in migration blocking per group and round, effective blocking, at least €1 invested per round, is shown for rich country (red).

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in